Is Britain Becoming The Third Sick Man Of Europe?

Why the UK is facing a double-barreled threat of slow economic growth and soaring public debt

In a previous article, I suggested that France’s massive debt, and its political doggedness in refusing to fix it, has put the French at risk of becoming the new sick man of Europe. The original contender for the title was (and perhaps still is) Germany, who instead took budget prudence to the extreme — resulting in consistent, low-to-negative economic growth since the pandemic.

But now, the United Kingdom is facing a similar problem on its horizon. All eyes will be on Rachel Reeves, who will deliver the budget on 26 November. While lobbyists will likely be fighting for her attention during the Labour Party conference this week, Reeves only has one group of people to watch out for: bond traders.

Fiscal sustainability

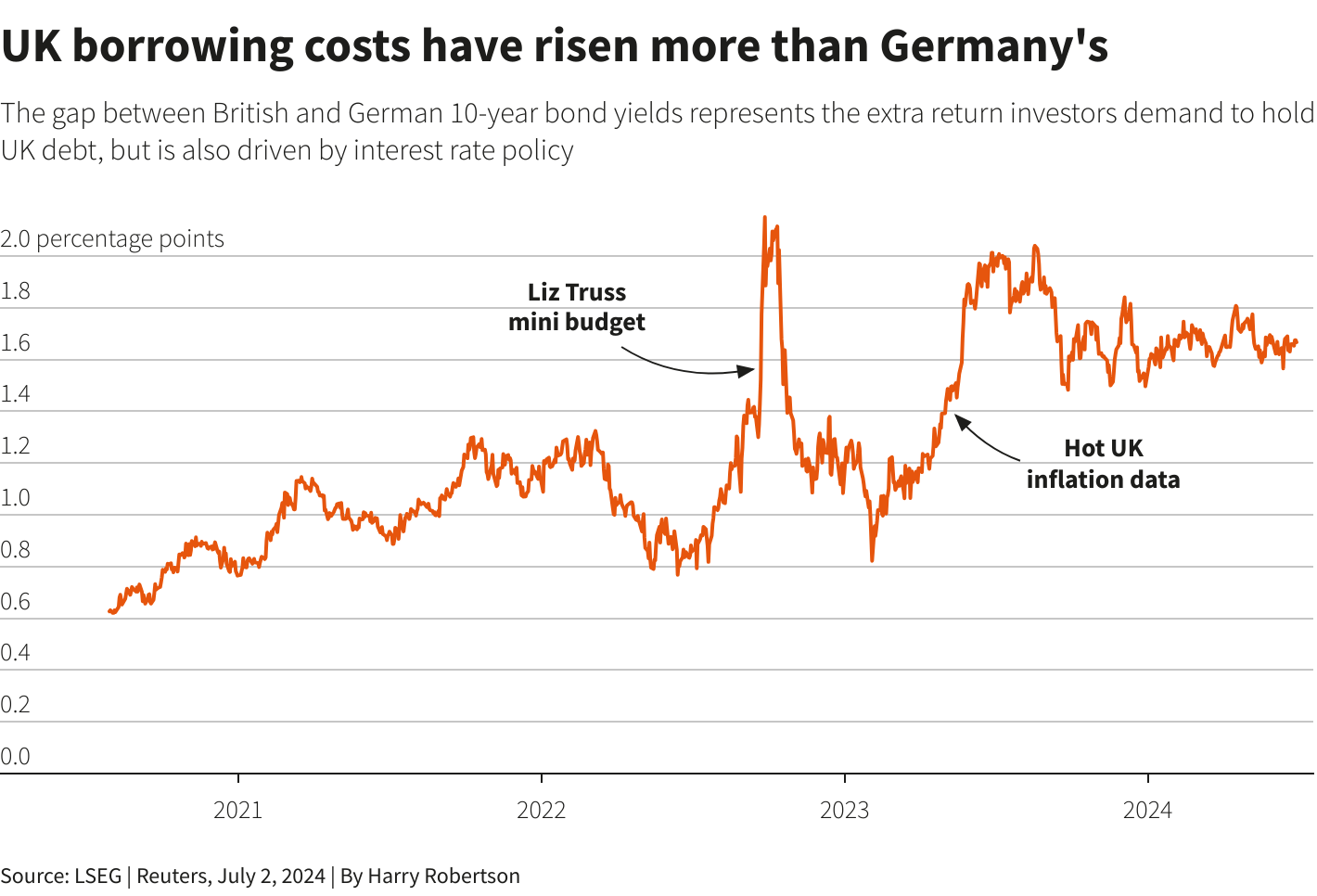

Liz Truss’s mini budget crisis in late 2022, and her resulting short-lived premiership, should be seared into the British collective memory. During the depths of the crisis, where Truss announced a chaotic package of large, unfunded tax cuts, the yield on 10-year British bonds (called gilts) jumped by 50 bps (or 0.5%) in a single day. The reason is trust. If the British government is seen to be fiscally irresponsible, holders of British debt will be quick to sell them. As bond prices drop, yields rise due to their inverse relationship.

The massive leap in bond yields had scuttled Truss’s premiership. High rates mean that Britain now needs to pay higher interest on their debt, which has more than doubled in the past five years. In August alone this year, interest payments on government debt were £8.4bn. From 2025-26, the Treasury is expected to spend a total of £111bn on interest payments — higher than the education budget. Beyond that, Britain also now has the highest yields across the G7, a group of wealthy countries. Compared with just 0.20% in 2020, gilt yields have now reached 4.8%.

But how do you lower gilt yields? One mechanism is to cut rates, a tool that the central bank, the Bank of England (BoE), can wield. To that end, the BoE has been reluctant, holding interest rates at 4%, double the level set by the European Central Bank (ECB). The reason: sticky, high inflation. Prices have risen 3.8% in August this year, and inflation is projected by OECD to be the highest among the G7. In the Eurozone, inflation stood at just 2.0% last month. Furthermore, the BoE has already cut rates five times this year. Further cuts risk making inflation even stickier.

Another way is to inspire fiscal confidence. In this regard, Reeves has yet to do so, walking back on welfare cuts as well as increasing winter fuel payments during the summer. Failure to bite the bullet is made all the worse by the ostensible fact that Britain has spent way too much on benefits — in particular, pensions. Britain is forecasted to spend 10.6% of its GDP on welfare this year, and more than half that goes to pensioners. The triple lock arrangement (which guarantees pensions goes up annually in line with inflation, wage increases or 2.5% — whichever is the highest), coupled with an ageing population, ensures that this avenue of spending will only get worse.

Spending cuts are politically unpopular, as Labour had found out. The alternative is raising taxes. The problem is that Labour had promised, before it was elected, to not raise taxes on consumption and income. That leaves it little room to manoeuvre. Reports have suggested that Reeves could introduce a national property tax, replacing stamp duties and council taxes to make up the £41bn shortfall.

Worse still, a budget failure in November might give the right-wing Reform party some political ammunition, which threatens to plunge the UK into even greater financial ruin. The Reform manifesto promised to slash £90bn of income tax cuts, and increase spending (in particular, defence) even further, widening the deficit.

Flagging growth

A problem presented by bad public finances is that Britain has nothing to show for it. Unlike the US, which is protected by both its status as the world’s reserve currency and its robust economic growth, Britain has little to cushion the impact of a bond rout. Even France is somewhat protected by the ECB, which can purchase French bonds if yields become too high.

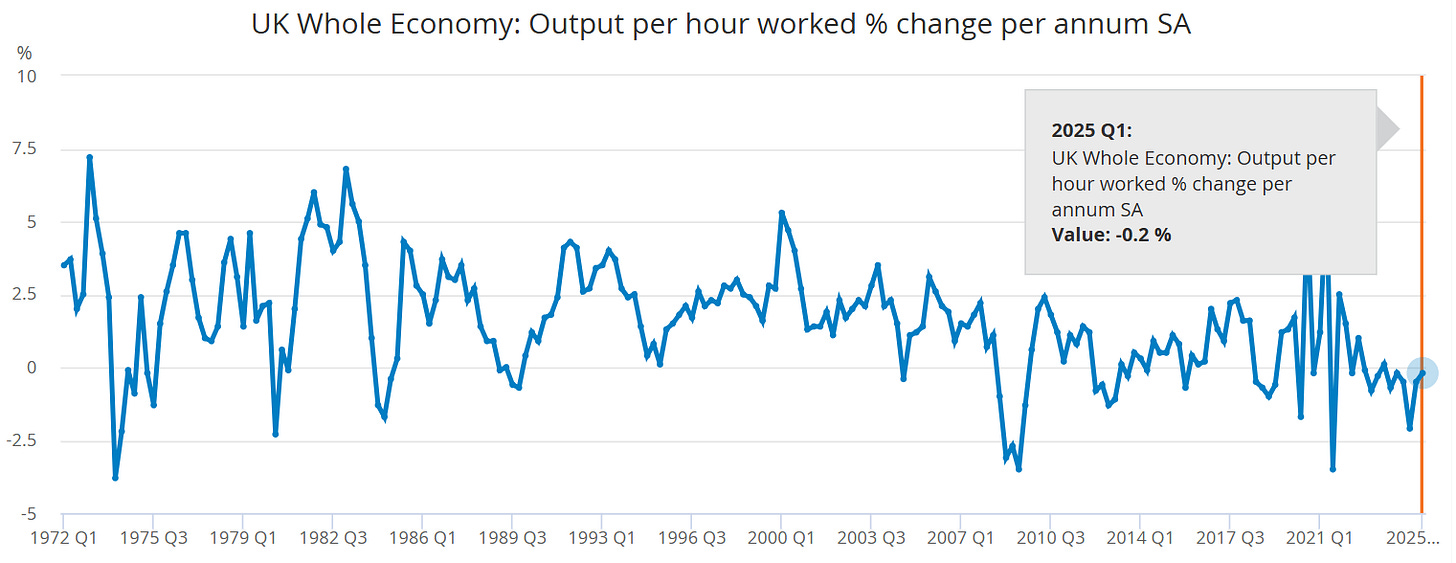

Fifteen months into office, Labour’s growth mission had stalled. Brexit aside, Britain’s productivity growth has not only been stagnant, but is on the decline since the 1970s. Britain is also overly dependent on its most productive city, London, for carrying much of its economic growth. But the largest foreteller of economic growth is housing. New housing starts in the UK were up 11.3% in the first quarter of 2025 according to ONS, but were down by more than 26.7% compared to pre-pandemic numbers in 2019. David Crosthwaite, an economist at BCIS (Building Cost Information Service), said:

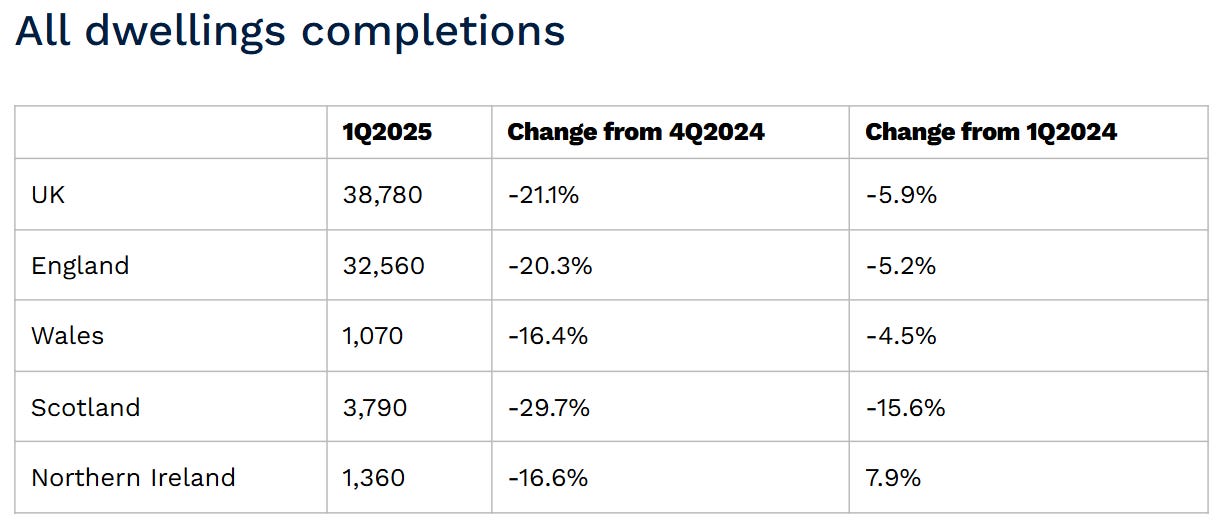

The data for completions is even more concerning and highlights the real struggle the government is going to have regarding the delivery of 1.5 million new homes over the life of the current parliament.

Even worse, in contrast to starts, UK housing completions in 1Q2025 were down both on the quarter and the year, and is the lowest number recorded since 2016. In London, the situation is even more extreme. According to the Economist, two-thirds of London boroughs started no projects of 20 or more homes. Altogether, demand for housing is just weak, likely due to high interest rates. Even if there is demand, housing developers face a deadly chokehold from both NIMBYism and Green Belt restrictions.

Government investment also has little to show for. One of London’s biggest pain point, Heathrow Airport, is busting at its seams with only two runways for the amount of commercial passengers it receives. For comparison, Denver International Airport, the next busiest airport, has six (!) runways. Despite the House voting in favour of the third runway in 2016, construction has not even begun. Conservative estimates put completion dates at around 2040. Another plan to convert Britain’s darling university cities into innovation hubs, labelled the “Oxford-Cambridge Arc”, has similarly stalled.

Down, but not out

In many ways, British exceptionalism still exists. It is home to the world’s best universities, and London remains the world’s largest foreign exchange and insurance hub by a good margin. But if Reeves cannot procure a responsible budget by November, then the bond markets are sure to express its discontent — and the country as a whole will suffer for it.

Reeves need to tell Bailey to stop QT its a pointless endeavour that is only adding to borrowing. Its criminal that he has been selling bonds that he bought for over a 100 at less than 30. She also needs to go after pensioners now big time and adopt the sensible idea to cut NI by 2% and put it on oncome tax instead. Thus pensioners and any