Why France Is Looking A Bit... Italian

Amidst high deficits and political instability, short-term bond yields for France have now exceeded Italy's.

When I was visiting Paris last year, the usual 1.5 hour bus ride from Beauvais Aéroport to Porte Maillot became a 3 hour detour instead. The reason was very French: protests. In particular, farmers blocked roads into the French capital using tractors, in an objection to various agricultural policies. Just the previous year, France saw more than a million protesters nationwide in response to Macron’s pension reforms to raise the retirement age.

One wonders if the French government is purposefully courting chaos: last week, Prime Minister Bayrou brazenly announced abolishing two public holidays, amongst other fiscal measures. He suggested Easter Monday and VE day. This will unironically further hinder France’s productivity with even more protests. Even if it’s just a media distraction, there is already fierce backlash from both the left and the right, and a vote of no confidence now looms over Bayrou when the parliament convenes in September.

Les déboires politiques

France’s political woes started way back in 2022. Macron’s Renaissance party lost its absolute majority in the 2022 legislative elections, which meant that it needed support from other parties to pass legislation. Then-PM, Borne, unable to muster political support, had to resort to an arcane constitutional provision, Article 49.3. This allowed the PM to pass a bill without a vote in the National Assembly, unless a motion of no confidence was passed within 48 hours. Ostensibly, this wasn’t politically sustainable (Borne triggered the Article 23 times over 20 months), and Macron’s popularity plummeted.

Attal, a young and popular candidate at that time, was appointed to replace Borne. Macron, in a risky gambit, called a snap election in mid-2024 after poor results in the European Parliament elections. This failed, and the Renaissance party lost 86 seats. Attal offered his resignation, and Macron appointed Barnier, who tried to get support from the National Rally to pass a new budget — which again, did not work — and tried to invoke Article 49.3 to force it through. A no-confidence vote was triggered, which Barnier proceeded to lose just 3 months into the job. This brings us to Bayrou, the current PM, who then narrowly survived a no-confidence vote in January, but after agreeing to suspend Macron’s unpopular pension reforms.

Italy has experienced a period of relative political stability, with PM Meloni and her center-right coalition holding an absolute majority since 2022. In the same number of years, France has cycled through 4 prime ministers.

Ballooning deficit

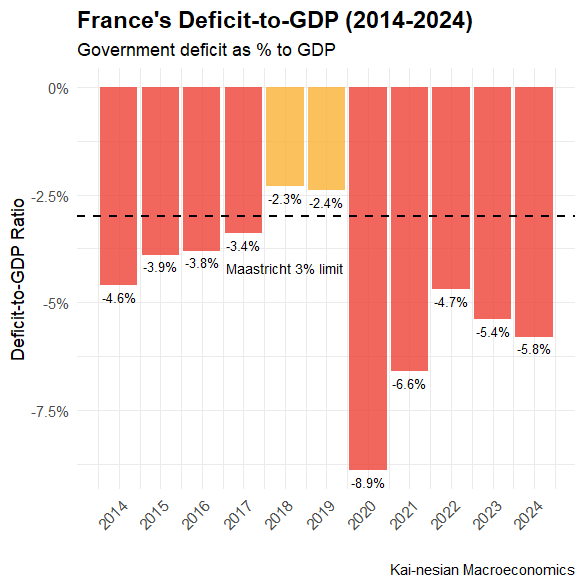

The largest reason for France’s political mayhem is likely its massive deficits. France has long ran high public spending, especially after Covid in 2020. The deficit-to-GDP ratio has since recovered from an astronomical 8.9%, but the trend is reversing. In 2024, tax receipts rose only 3% even as spending grew 3.9%, resulting in a €169.6 billion deficit.

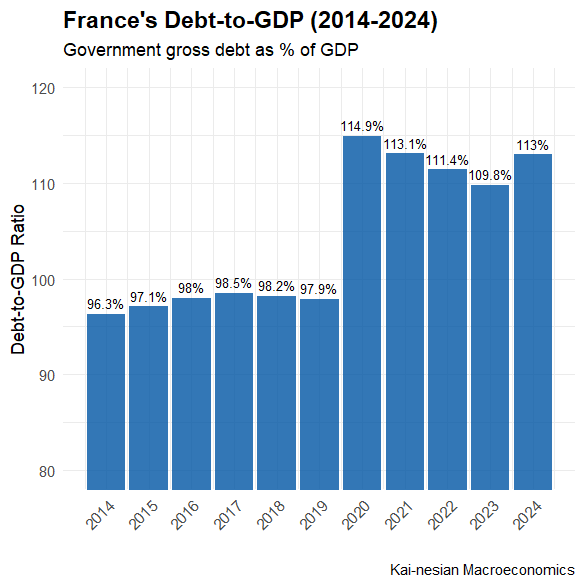

In my previous article, I mentioned that debt growth is okay, as long as the economy is growing alongside it. France’s debt-to-GDP ratio has actually been on a downwards trend as it recovers from high Covid spending, but 2024 saw it shot back up to 113%. The reason is sluggish growth. France’s economy grew by 1.1% in 2024, which is (very slightly) below the EU average. The forecast for 2025 is even worse; with GDP growth expecting to slow to 0.6%.

Only two countries in the EU have higher debt-to-GDP levels; Italy and Greece. The latter is infamous for its 2009 debt crisis, and Italy has always been labelled as Europe’s fiscal basket-case. But the difference between France and Italy is that the Italian deficit is on a consistent downwards trend. In 2024, its deficit-to-GDP is 3.4%, which is down from 7.2% in 2023. In 2025, the deficit is projected to be even lower.

France, meanwhile, is on a spending spree. Bayrou, in his budget press conference, announced, “We have become addicted to public spending.” This is not an exaggeration. But what does France even spend on? More than half goes to social welfare programmes: pensions, unemployment and aid. This portion is set to increase as France, like every other developed country, suffers from an ageing population. Another 20% goes to public sector wages, which Bayrou is targeting in his proposed budget (3,000 civil servants position to be cut, and a third of retiring civil servants to not be replaced).

Aggravating the budget is defence spending. This is something that France shouldn’t be faulted for, however, as Russia continues to encroach incrementally into Europe. The defence budget would total €64 billion in 2027, effectively double the defence spending in 2017. It is also the only line item that would see an increase in Bayrou’s budget.

The yield spread

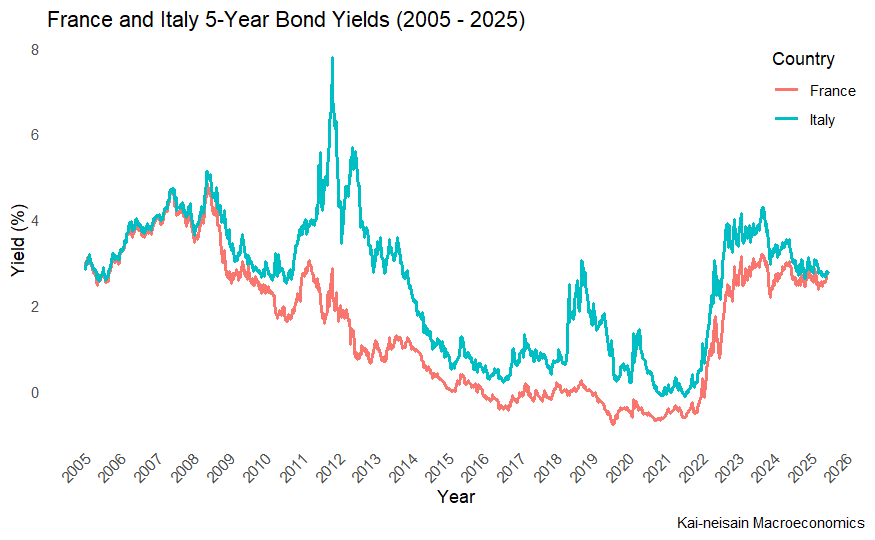

Governments issue debt (in the form of bonds) to raise money for spending. Across bonds with the same tenor, economists can examine the yield differences between countries to estimate the market’s expectations for the likelihood of default. It stands to reason that the riskier the bond-issuer is at defaulting, the higher the yield expected to compensate for the risk.

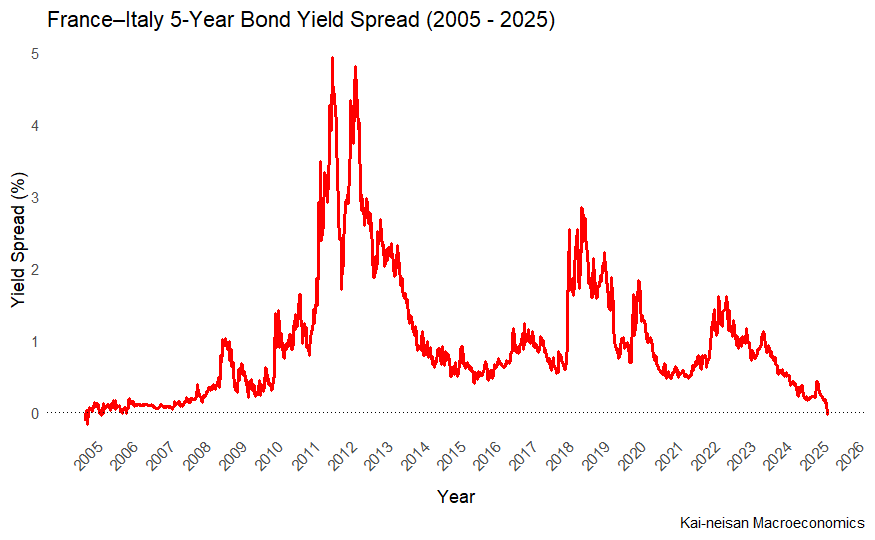

For a very long time, the yield on Italian bonds (known as BTPs - Buoni del Tesoro Poliennali) has always been higher than French bonds (OATs - Obligation Assimilable du Trésor). The exception to this are short-term yields. Toby Nangle, a columnist for the Financial Times, noted that two-year BTPs infrequently traded through two-year OATs back in May this year, and briefly at the start of 2024. But such short-term yields are highly sensitive to monetary policy (or even expectations of monetary policy). Sudden surges in demand can also push 2-year yields down, even if underlying fundamentals haven’t changed much.

A more enlightening graph to look at are 5-year bond yields:

For almost two decades, the bond yield spread (difference between BTPs and OATs yields) have been positive, indicating that Italian debt is riskier to hold. But just last week, the yield spread has dipped into negatives. In March this year, credit rating agency Fitch assigned a rating of ‘AA-’ with a ‘negative outlook’ to France. In comparison, the U.S., with its enormous debt, received a ‘AAA’ rating.

Higher bond yields not only makes it more expensive to issue more debt, but also to service existing debt. To service the higher interest on existing debt, it is tempting to… issue even more debt, leading to a quasi-debt spiral.

The sick man of Europe

The label was first pinned on the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, a metaphor for imperial decline. It later attached itself to Britain, whose postwar deindustrialization lost its superpower status. Today, it hangs over Germany, where economic stagnation has become a defining feature of the 2020s.

France edges towards insolvency. Europe can ill afford two sick men.