If Not Dictator, Why Dictator-Shaped?

A scrutiny of the modern strongman: the global resurgence of autocratic leaders, and why people find authoritarian rule so appealing.

Examine the strongman leaders of today. Among the rich countries, you have Donald Trump, who encouraged Americans to inject bleach and claimed Tylenol causes autism; and Boris Johnson, who became the first (and only) British Prime Minister to resign because he was ‘ambushed by a cake’. In the developing world, you have Bolsonaro who linked vaccines to AIDS, Duterte who openly boasted of killing people, and Modi who suggested that cloud cover could help Indian jets escape enemy radar. The unifying trait that these world-shaping charlatans have, uncannily, seems to be how ridiculously inept they are.

The question is how they manage to get into power in the first place. Moisés Naím, author and distinguished fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, posited that these strongmen are driven by “Three P’s”: populism, polarization, and post-truth. The modern strongmen favour stealth — the flashy military coups and insurgent uprisings of old seem to have gone out of vogue. They usually start out elected as a prime minister, president, or whatever, and the initial election is mostly fair. But the moment they get into power, they start to make decisions that undermine democracy.

Vox Populi(sm); Vox Polarization

One of the strongman modus operandi is tapping into something primal in us: a tribalistic need for belonging that goes way back to the campfire. The world has changed enormously in the past couple decades. A non-trivial amount of people feel increasingly alienated by the new world, and have lost their sense of belonging. Strongmen appeal to this baser instinct. It is the same sort of thing as nostalgia, a nod to the notion that the past was “better,” and that society needs to return to some sort of “good old days”. Promising that, a lot of people will ignore or outright justify whatever surrender of personal liberties is deemed “necessary” to achieve that.

We see this in the heart of Europe, where Putin’s imperialistic, revanchist zeal attempts to harken to the old glory of the Russian empire. The Putin narrative is that the Russian people have been alienated from the world, and that only he, Putin, can protect and defend them. In the case of Chancellor Mustache, he sold Germans an Aryan mythos. In the case of MAGA, it’s a mix of convincing people the past was better, either by downplaying how awful things like Jim Crow laws were, or in the case of the most outwardly racist elements, just nakedly embracing these things. Kati Marton, a Hungarian journalist, summarized it well: strongmen re-edit, revise, re-mythologize their own history to make it seem as if there was a golden age, when in fact no country has ever had a real golden age.

One does not have to look far for proof. Trump’s very inauguration speech reads:

The golden age of America begins right now. From this day forward, our country will flourish and be respected again all over the world. We will be the envy of every nation. And we will not allow ourselves to be taken advantage of any longer.

Another important part of the ploy is victimhood. We saw this dynamic explode on January 6, 2021, when followers felt their strongman leader was in distress. Playing the victim not only demonizes the strongman’s enemies but also allows followers to feel protective of him. At some fundamental level, the January 6 insurrectionists knew their actions were, at best, unusual, and at worst, treasonous (many faced charges for ‘seditious conspiracy’). However, the perceived injustice; the idea that their leader was ‘unfairly’ ousted from power, justified their actions. Trump’s message on that day was essentially: My election has been stolen. You have to fight, or you won’t have a country anymore. And fight, they did.

Lastly, fascism is to some extent the politics of pride. It is an ideology that tells people they are special, they are better than others, and they deserve to be elevated over others. Who doesn’t want to be told they are special? For people who maybe feel that society isn’t fair to them, or that others are taking what had traditionally been their opportunities or privileges, the strongman can be appealing. Trump’s crusade against diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) underpinned a cornerstone of his second campaign. In its most benign interpretation, the DEI scapegoat served to elevate the white voter base and make them feel special; however, the truth is that it simply gave people the permission to be nakedly racist.

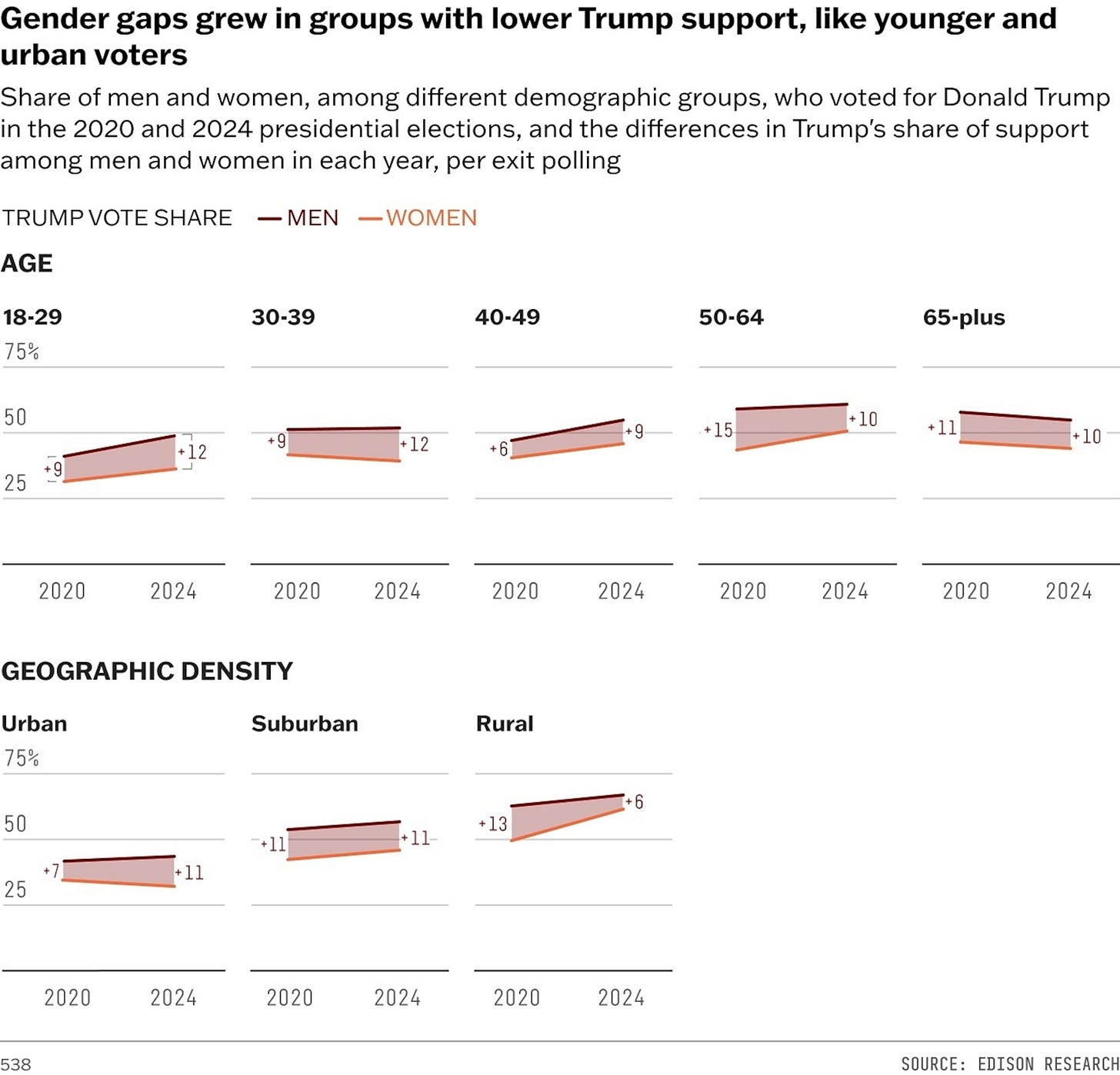

We see this effect especially pronounced in the way males voters behaved:

The demographic most receptive to Trump’s anti-DEI rhetoric appears to be young men, many of whom feel intense pressure to meet traditional standards of masculinity. This is especially true for Gen Z men, who face an economy they perceive as excluding them, with reports indicating that one in five young men are currently jobless. For those in the ‘manosphere,’ DEI provides a convenient target onto which they can project their economic and social frustrations. This electoral anger is consequential: as the data shows, the largest proportional increase in vote share between 2020 and 2024 was seen among young urban men (who likely face the stiffest job competition).

Agnieszka Graff, a Polish scholar at the University of Warsaw, agrees. In a short essay to Moment magazine, she wrote:

People who vote for strongman leaders such as Trump, Meloni and Orbán feel they have been humiliated and looked down upon, and that now is their moment of revenge.

Strongmen speak to the people who say racist things but don’t think of themselves as racist. They speak to the stay-at-home moms who are sick of being told that they should have a career. It’s the anger of ordinary people who have had it with the liberal elites.

The weakness of liberal democracies

Liberal democracy has been far too blithe about its strengths, suffering from a critical deficit in self-preservation. Consequently, many of the new authoritarians were initially dismissed as harmless. From such naivety bred complacent policies that have helped the new authoritarians on their way: from Germany’s ill-judged self-subordination to Russian energy interests, to Macron’s unnecessarily arrogant and haughty style of leadership playing into Le Pen’s hands, to the Democratic party in the US blithely writing off Trump’s chances of defeating both female candidates and subsequently governing in the chaotic style in which he had campaigned.

Gideon Rachman, the chief foreign affairs columnist of the Financial Times, divided events since 1945 into three cycles: the postwar boom years, the ‘neoliberal’ era from the 1970s to the financial crash, and the post 2008 ‘age of the strongman’. We see this in Latin America, where the democratic transitions of the late 1980s and 1990s sparked a period of optimism about the possibilities of democracy. Around 2000, this coincided with an enormous commodity boom, driven by massive Chinese demand for raw materials (such as iron ore, copper, and soy). This boom occurred during a period of leftist governance, featuring figures like Venezuela’s populist and quasi-authoritarian Hugo Chávez, alongside social-democratic leaders like Michelle Bachelet in Chile. Utilizing the commodity income, governments across the region adopted policies that successfully lifted millions out of poverty.

With the 2008-2009 financial crisis, this boom started to erode. Frustration grew as people fell back into poverty. In 2019, Chile, once seen as the poster child of stable governance, consensus-based politics and sound macroeconomic policy, saw the largest demonstrations since the fall of its military dictatorship in 1990. At the same time, several mega-corruption scandals came to light. People lost faith in democracy’s ability to deliver and to protect them from violence, including gang extortion and threats.

Fighting criminal violence was what made President Nayib Bukele of El Salvador immensely popular. While Bukele did actually lower gang violence, it’s hard to wholeheartedly embrace the draconic measures he used to do so: gutting the judiciary, deploying the military to arrest civilians (sounds familiar?), and shepherding people into mass prisons without legal recourse.

(Perceived) state failure

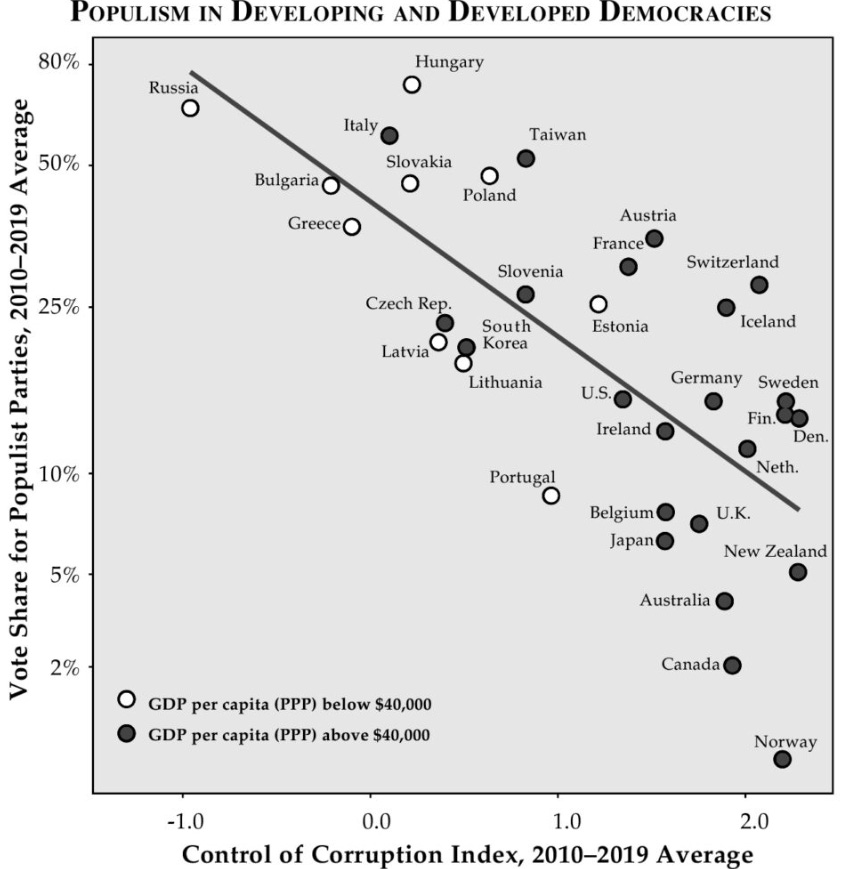

Roberto Stefan Foa, a politics lecturer at Cambridge, posited in an article that state failure, even if perceived, gave rise to authoritarians. In fragile democracies, strongmen are able to sweep into power by stimulating the desire for public order, accountability and an end to graft. Such leaders tap into a broader swell of anti-establishment sentiments — beyond their usual ideological base — adding legitimacy to their populist cause.

In many developing countries, this corruption, criminality or state failure become a fertile breeding ground for strongmen to thrive. We saw this in a previous example with President Bukele. In the Philippines, a sense of physical insecurity among the country’s urban population, shaken by a homicide rate that has soared in the last decade, helps to explain why between eight out of ten Filipinos continue to support Duterte’s brutal “war on drugs” despite its heavy toll in lives lost and rights violated. And in Brazil, almost 70 percent of voters in São Paulo state voted for Bolsonaro in the 2018 presidential runoff not because of any newfound distaste for homosexuality — the state’s capital has hosted the world’s largest gay-pride parade annually for almost two decades — but due more to widespread disgust with political corruption, despair at the persistence of urban crime, and sympathy with calls for harsh measures to restore “order and progress.”

Notably, this “failure of the state”, be it crime, corruption, drugs or gang violence, does not even need to be real. Trump campaigned off the fact that USAID was a “tremendous fraud”, stealing “billions of dollars”. The administration also gutted the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and fired thousands of federal employees. Were all of these really government waste? Likely not, but it doesn’t matter. People believed in it, and it gave legitimacy to the narrative.

A vote for the strongman is a vote to “get stuff done”. Not just aforementioned corruption, but for red tape as well. Prior to the strongman, nothing ever gets done because “they” get in the way. “They” can take the form of anything from judges to the media, to landowners to businesses to people with brown skin. The strongman promises to push all obstacles out the way and get stuff done, and if the “stuff” being proposed sounds good to you (say, “eliminating waste and fraud”), then the idea of an all-powerful leadership which brooks no opposition is a welcome alternative to bureaucratic inertia.

Strong men, weak outcomes

A well-functioning bureaucracy follows established rules to prevent abuse of power and constrain executive behaviour. For this very reason, the bureaucracy is the very first thing item on the strongman’s hit list once they come into power. For instance, following a failed coup in 2016, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan fired and detained around 100,000 government workers. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, after returning to office in 2010, ordered mass firings of civil servants and installed allies of his party in critical roles. As former Hungarian minister Bálint Magyar once written in 2016:

While the mafia state derails the bureaucratic administration, it organizes, monopolizes the channels of corruption and keeps them in order.

In Venezuela, President Hugo Chavez removed scores of civil servants, on the basis of whether they were political dissidents. His successor, Nicolás Maduro, immediately performed a similar purge under the banner of anti-corruption.

The reason why purging the bureaucracy is dangerous is because strongmen often replace them with sycophants. Ruth Ben-Ghiat, a professor at NYU who wrote Strongmen: From Mussolini to the Present, calls this phenomenon “autocratic backfire”, where strongmen believe in their own propaganda. Over time, they stop listening to the experts, and the quality of decision-making will likely go down. While every strongman styles himself as a stable genius, the truth is that illiberal leaders, especially when surrounded by sycophants, are prone to grievous errors. History is not short of these examples: Hitler’s catastrophic march to Moscow, Mao’s disastrous Four Pests campaign, Xi’s obsession with Covid-zero, or Putin’s miscalculations in invading Ukraine.

In the long run, strongman rule is often deleterious for the economy as well, as it distorts the market and erodes the institutions that a functioning economy depends on. For instance, Trump’s tariffs have already shifted global trade patterns, some of which permanently, away from the United States.

The silver lining

It is by no means inevitable that, once democratic backsliding happens, a country will continue until it reaches authoritarianism. Though democratic consolidation is difficult, authoritarian consolidation proves a great deal harder. Not only are populist strongmen weakened by their personalistic nature and vulnerability to leadership changes, but internal factions may also be surprisingly receptive to political liberalization. The past decade, marked by the steady defection of liberal reformists from Putin and Erdoğan administrations, confirms this vulnerability.

Evidence suggests that strongman rule usually ends badly for individual countries. It makes the international arena more turbulent, illiberal and unpredictable. A strongman system won’t lack for excitement. But as the saying goes, the only good politics are boring politics.

This is a really good article. I especially appreciate your pointing out the oh-so-true fact that elites (including myself) fell into the illusion that once people SAW how crazy and reckless Trump is, they would surely, certainly! fall away from supporting him. I have learned so much.

I've grown particularly interested in how the US economy will finally land. AI and $$$ tech are creating an infinitely booming stock market while the common man's dollars can cover less and less and less of their expenses, AND all social safety nets are being pulled away. When do these two things clash?

Thanks for your insights!

Great writing. I’m reminded of Professor Jiang’s lectures