The Pessimist's Guide To ASEAN Summits

Why the ASEAN bloc struggles to find consensus on key regional issues.

As a Singaporean, it is easy to be skeptical of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN). All too often, the ten-member bloc sidesteps the regional elephants in the room. Yet on 26 May, ASEAN leaders gathered in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, for their biannual summit — remarkable not for its location, but for its unprecedented guest list. For the first time, both China and the six-member Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) joined the table, signaling an openness in ASEAN’s outreach.

The (Burmese) elephant in the room

ASEAN treats the Myanmar problem like a migraine: chronic, and easier to ignore until the next flare-up. For four years since the military junta’s coup d'état in 2021, ASEAN has continuously failed to move beyond platitudes. At a summit in Jakarta on April 2021, ASEAN leaders and Myanmar junta chief, Min Aung Hlaing, agreed to five points, or the “Five-Point Consensus". The first point calls for an immediate end to violence in the country. Two days later, the junta reneged its endorsement and ramped up its abuses, including mass killings, torture and attacks on civilians.

To Malaysia Prime Minister Anwar’s credit, who chaired this year’s ASEAN summit, he met with Min after the devastating earthquake in March to secure an extension of the junta’s ceasefire. PM Anwar reported that he was given an assurance that the ceasefire would hold. NUG, the shadow government formed in response to the coup, reported that junta airstrikes conducted since the earthquake has killed at least 334 civilians, including 53 children. ASEAN’s response was a strongly worded letter.

Perhaps as a slap in the face, while ASEAN leaders were meeting in Kuala Lumpur on Sunday, another junta airstrike hit a small town in Kyaukkyi, Bago region, killing at least 10 another people.

PM Anwar opened the summit with this:

"We have been able to move the needle forward in our efforts for the eventual resolution of the Myanmar crisis…

…I wish to stress that throughout this process, quiet engagement has mattered. The steps may be small and the bridge may be fragile but as they say, in matters of peace, even a fragile bridge is better than a widening gulf."

I think it’s obvious that ASEAN has no intention to play hardball with regards to the Myanmar issue. What can ASEAN do anyway? For one, they can revoke Myanmar’s membership, although precedence states that no such thing will happen — ASEAN sat on their hands while Thailand went through a coup in 2006. Alternatively, they can place travel bans on junta leaders, freeze assets, and impose targeted sanctions. Again, this is borderline impossible, as Singapore is likely to veto against it, as they had invested over $456 million in Myanmar projects just last year. Singapore, being the region’s petrochemical hub, also has close dealings with junta-controlled Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE).

The China problem

If you think the Myanmar situation has dragged on, the South China Sea dispute is even more protracted. For decades, China had claimed the majority of the South China Sea as its own, whereby a large chunk of the maritime ocean is demarcated by an infamous “nine-dash line”.

China’s claim stretches all the way to James Shoal, a submerged bank a mere 80 kilometers away from Borneo Malaysia and a comical 1,800 kilometers from China. That is not where the action is, though. In 2024, China markedly increased tension near the Second Thomas Shoal, a short distance away from the Spratly Islands. Operating within Philippine’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), Chinese sailors armed with axes, pikes and knives assaulted Philippine marines, destroyed communication equipment and punctured the hull of a Filipino resupply vessel on 17 July 2024. Later that year in December, a Chinese Coast Guard vessel fired high-pressure water cannon at a boat carrying supplies to Filipino fishermen at Scarborough Shoal.

Although confrontations were never again as violent as that of 17 July, China still routinely harasses Filipino vessels in the South China Sea. Just two days before the ASEAN summit, a Chinese Coast Guard ship fired water cannons at marine research vessels off Sandy Cay reef, damaging the ship’s port bow.

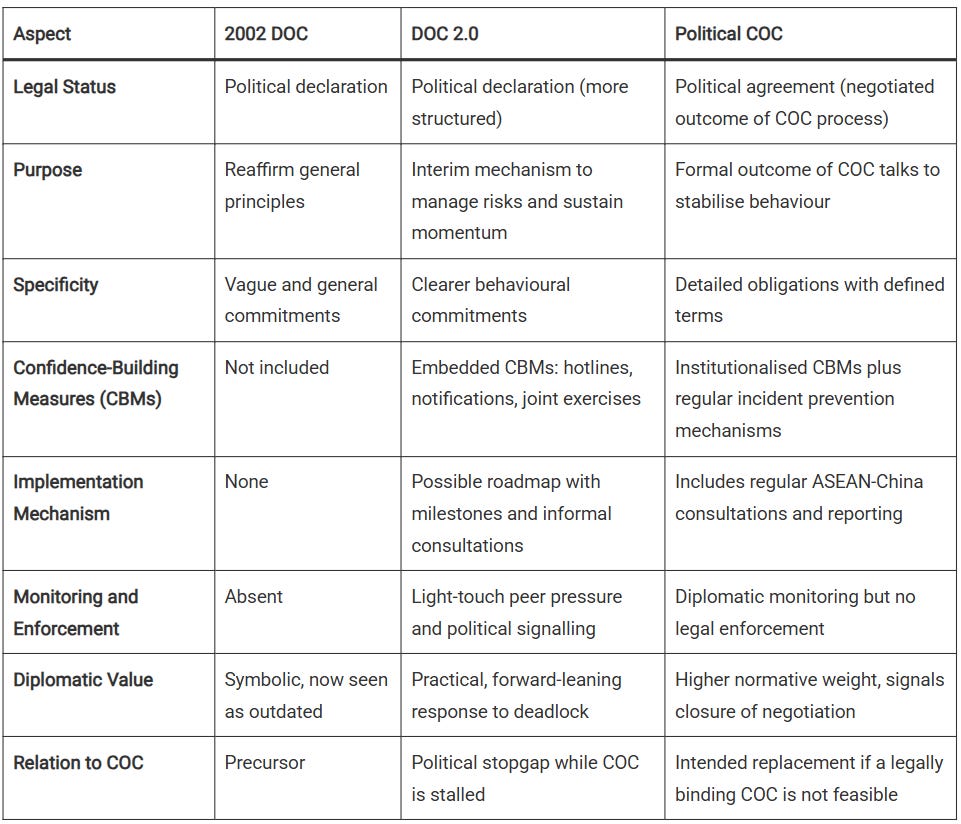

ASEAN’s response has been a laggard one. When confronted with China’s maritime assertiveness, ASEAN leaders frequently reference the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea and the still-negotiating Code of Conduct (COC). The COC has stalled repeatedly over the years. During the inaugural ASEAN Maritime Security 2025 forum in Manila, an anonymised poll was conducted on the likelihood of finalising the COC. Only one person thought the agreement would be wrapped up within three years. Eighteen predicted it might take a decade, while the majority — 28 participants — said the code “will never be completed”.

The problem lies with ASEAN’s consensus-based approach to decision-making. Based on the ASEAN Charter, agreement from all member states is required for all major decisions. When North Korean torpedoes sank a South Korean corvette in March 2010, ASEAN's response was muted. In early 2016, for example, ASEAN foreign ministers didn’t express concern after Pyongyang detonated a hydrogen bomb. This weak stance is largely due to the sympathy some ASEAN members hold for North Korea, making a unified ASEAN response difficult.

Even if ASEAN is able to unify on the China front, any progress will be halted by China itself. China prefers a non-binding flexible COC that avoids external scrutiny and monitoring, while (most of) ASEAN seeks a robust, legally-grounded agreement. Joanna Lin and Pou Sothirak of the Yusof Ishak Institute proposed an intermediary solution that functions as a diplomatic stopgap between the 2002 Declaration and an ideal COC:

Even so, progress will be slow, if any. The ASEAN way — quiet diplomacy, non-interference, agreement by consensus — is time-consuming and hampers collective action. That being said, ASEAN summits are not merely platforms for grandstanding. They are also a hub for bilateral deal-making. On the sidelines, an agreement was inked between Singapore, Malaysia and Vietnam to export renewable energy from Vietnam to its southern neighbours. Timor-Leste is likely to be formalised as the eleventh member in October. Singapore and Indonesia will walk away with a new undersea electric cable laid between the two countries.

But in the meantime, ASEAN summits will continue to kick the Burmese and Chinese cans down the road. The Pessimist’s Guide to ASEAN Summits will end aptly with a quote from Douglas Adams:

“For a moment, nothing happened. Then, after a second or so, nothing continued to happen.”

- The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy